Tragedies and Transformations

- Richard Byrne

- Aug 7, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 11, 2025

One of my most prized possessions is a signed copy of I Was a German — the original 1934 English translation of Ernst Toller’s memoir.

To have any object that Ernst Toller once held in his hands and signed is special. But what makes the book even more meaningful to me is that it was inscribed for future New York Times foreign correspondent Cyrus Sulzberger (who was only 27 at the time) on January 19, 1939.

ul

zberg

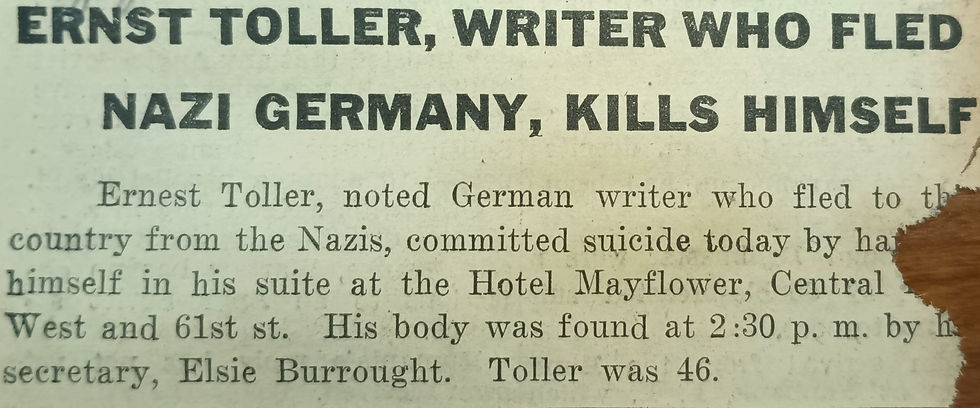

Why is that date so special to the author of the play Hotel Mayflower? It was on that precise day that Ilse Burroughs arrived in New York City on the MS Vulcania — which is one of the key inciting incidents in the play.

So, as an object, this book is priceless to me. But as with any English translations of Toller’s plays, poetry, or prose from the 1920s and 1930s, there is significant room for modernization and improvement.

Among the numerous factors that came into confluence after Toller’s suicide in 1939 to dim his literary reputation is that existing English translations of his plays were both mannered and production-unfriendly in the U.S. theatre of mid-century and beyond. It was a problem that Toller recognized even before his death. His final months saw an effort to create a new version of his final play, Pastor Hall, to replace a Stephen Spender translation that some theatre professionals found unworkable.

Thankfully, new published translations of Toller’s plays by Alan Raphael Pearlman, Peter Wortsman and Drew Lichtenberg have gone some ways in bringing a fresh view of Toller’s stagecraft to public view.

Yet in the present burgeoning renaissance of interest in Toller’s life and work, it is also welcome news that a new English translation of that book published in the 1930s as I Was a German has appeared recently.

The new translation by Eoin and Eva Bourke restores Toller’s original title for the work: A Youth in Germany (Broadview Press) It is a narrative that moves deftly from the author’s childhood and young adulthood through his brutal experience of World War One and his extraordinary rise to political prominence in the ferment of Germany’s revolutions of 1918 and 1919. A Youth in Germany concludes with Toller’s firsthand account of his time in prison as a result of his deep involvement in Bavaria’s failed Soviet Republic.

Editors Christiane Schönfeld and Lisa Marie Anderson also offer a sharp introduction and a wide-ranging collection of supporting texts that trace Toller’s influences and situate his tale in its historical context. Readers in 2024 will find this edition indispensable to understanding Toller’s life and work.

These readers will also find that the new edition features passages excised from the 1934 English translation by Edward Crankshaw. When I reached out to Anderson about what specifically was restored in the new edition, she mentioned that passages about threats Toller had received as a student in Heidelberg, as well as a number of his pungent observations about the functioning of Bavaria’s revolutionary government in 1919, had been placed back into the text.

But perhaps most importantly, Toller’s original introduction to the book —which had been broken up by Crankshaw and its publisher, Morrow, into a shorter preface and a final chapter — has been fully restored to its original position.

Anderson writes that her work with Schönfeld “was able to draw extensively on newly available materials from the critical editions of Toller's collected works (2015) and correspondence (2018). We prepared extensive paratexts that do a lot to contextualize Toller's chapters, including appendices that make some important documents of the period available in English for the first time.”

Grappling with Genre

So what sort of book is A Youth in Germany? As Schönfeld and Anderson mention in their introduction, Toller was the first to wrestle with this question. He had begun thinking about and drafting a memoir of sorts five years or so before the Nazi regime came to power in early 1933.

Yet it was the political cataclysm of Adolf Hitler’s assumption of power —and the subsequent abolishment of civil liberties in Germany by decree on February 28, 1933 after the Reichstag fire —that accelerated Toller’s completion of the project.

That he was able to do so at all was a stroke of good fortune. Toller was in Switzerland when Nazi authorities raided his apartment in 1933. He never returned to Germany. He spent much of the late winter and early spring of that year finishing the memoir.

From his exile, Toller became one of the most effective voices against the Nazi regime. And A Youth in Germany became a foundational document in that public opposition. He was thwarted in his attempts to publish the book in Switzerland before it appeared in as one of the first titles of the German exile press Querido Verlag in Fall 1933.

Toller’s desire to link his book to his opposition to German fascism was so powerful that even though he was working on it after the infamous burning of his books (and those of numerous other authors) at Berlin’s Opernplatz on May 10, 1933, he dates his introduction to the published book with the words: “On the day my books were burned in Germany.”

This linkage is highlighted by Schönfeld and Anderson as they analyze the competing claims of personal autobiography and historical narrative. In key aspects, global events inevitably transformed Toller’s account of his own journey as a historical figure into an actual work of history. This is particularly true of his accounts of war in A Youth in Germany —rendered in a deeply-compelling prose which supplements his plays and poetry about the conflict — as well as his personal recollections of his role in the Bavarian Soviet Republic.

The public controversies surrounding that failed revolutionary moment have lingered over a century after its eruption and demise. Other accounts situate Toller in those events differently than his own account in A Youth in Germany—and they draw alternate conclusions. Yet these chapters of A Youth in Germany do underscore Schönfeld and Anderson’s key point: Toller’s life had become history, and was woven inextricably with it.

And his account of it from his own perspective is invaluable.

A Powerful New Translation

Even in its previous version by Crankshaw, Toller’s narrative is vivid and gripping. Yet the new translation by Eoin and Eva Bourke intensifies these effects. (Eoin Bourke passed away in 2017 after he had completed a first draft, and the translation was complete by Eva Bourke.)

A Youth in Germany’s take on Toller’s classic is supple, vigorous and compelling. Overall, one notices that many sharp edges and vivid language polished away in Crankshaw’s version have been restored.

It’s useful perhaps to make some direct comparisons small and large. One of the most fascinating passages in the book—the almost immediate removal of Dr. Franz Lipp as the Räterepublik’s foreign minister—offers a clear contrast.

Almost as soon as he took his post in the new government, Lipp began sending wildly incoherent and inappropriate telegrams to world leaders. In Crankshaw’s translation, Toller quotes one of the telegrams and then writes:

Without a doubt, Lipp had gone off his head. We decided to send him immediately to a sanatorium, and to avoid a public sensation, to ask him to resign voluntarily.

The new translation offer something stronger and more pointed in style—making this episode simultaneously less comic and more urgent.

Undoubtedly Lipp had gone mad. We decided to commit him to a mental home straightaway. To avoid a public sensation, he must announce his resignation of his own free will.

When Lipp resigns, but somehow finds his way back to work to send more telegrams, Toller’s account gains more immediacy and force in the new translation:

He was kindly but firmly taken away (Crankshaw)

Orderlies carry him off from his workplace. (Eoin and Eva Bourke)

I also want to highlight a longer passage that conveys the lyrical heights which Toller’s prose touches in A Youth in Germany. In a chapter describing his experiences on the front near Verdun, there is a passage in which the author weaves the destruction of war, nature, and humanity into a knot of dazzling prose that matches any of his works as a poet or dramatist.

In Crankshaw’s version, this passage reads:

A devastated wood; miserable words. A tree is like a human being. The sun shines on it. It has roots, and the roots thrust down into the earth; the rain waters it, and the wind stirs its branches. It grows, and it dies. And we know little about its growth and less still about its death. It bows to the autumn gales, but it is not death that comes then; only the reviving sleep of winter.

A forest is like a people. A devastated forest is like a massacred people. The limbless trunks stare blackly at the day; even merciful night cannot veil them; even the wind is cold and alien.

Through one of those devastated woods which crept like a fester across Europe ran the French and German trenches. We lay so close to each other that if we had stuck our heads over the parapet we could have talked to each other without raising our voices.

We slept huddled together in sodden dugouts, where water trickled down the walls and the rats gnawed at our bread and our sleep was troubled with dreams of war and home. One day there would be nine of us, the next only eight. We did not bury our dead. We pushed them into the little niches in the wall of the trench cut as resting places for ourselves. When I went slipping and slithering down the trench, with my head bent low, I did not know whether the men I passed were dead or alive; in that place the dead and the living had the same gray faces.

The contrast between this version and the new translation below is startling. Not only does the passage regain descriptive force and syntactical rhythm in the Bourkes’ version, but the picture sketched by Toller is pushed into a more powerful clarity—just as a patient in an ophthalmologist’s office grasps the letters of an eyechart more clearly as the lenses are manipulated toward the correct prescription:

Ravaged forest—two miserable words. A tree is like a human being. The sun shines upon it, it has roots, the roots go down into the earth, rain waters it, winds waft through its branches, it grows, it dies. We know little about its growth and even less about its death. It bows to the autumn storms, it bows to its consummation. But it isn’t death that comes, it’s the sleep of winter.

A forest is a people. A ravaged forest is a massacred people. Armless stumps stand black in the daylight, and not even merciful night can conceal them, and the winds pass through them like strangers.

The German and French trenches run through Priesterwald, one of the many ravaged forests rotting away all over Europe. We are so near each other that, if we lifted our heads out of the trenches, we could talk to one another without raising our voices.

We sleep huddled together in muddy dugouts; water runs down the walls. Rats gnaw at our bread, while war and thoughts of home gnaw at our sleep. Today we are ten men, tomorrow eight—two have been mangled by grenades. We don’t bury our dead. We leave them in the small recesses that have been carved out of the trench walls for us to rest in. When I creep along the trench, I don’t know if I am passing a dead soldier or a live one. Here, the living and the dead have the same grayish-yellow faces.

Welcome New Context

The new edition of A Youth in Germany also includes 71 pages of notes and photographs that illuminate many sources and inspirations behind Toller’s masterpiece—as well as add valuable historical context for events described in the book.

The section on socio-political contexts provided for the book by Schönfeld and Anderson is excellent, and includes very pertinent information on the 1919 assassination of Bavarian leader Kurt Eisner which led the the formation of a revolutionary government a few weeks later. But newcomers to Toller and his work will find the section on literary influences and inspirations especially useful.

The inclusion of poems by often-ignored poets such as Franz Werfel and Richard Dehmel unlock a greater understanding of the book’s first nine chapters for readers. And given the enhanced fidelity and literary style of the new translation, the addition of poems by Toller himself is especially welcome for ready comparison.

As the story of Ernst Toller finds renewed attention in our own moment of resurgent fascism and debates over the role that art and literature and culture should play in politics, this excellent new translation of his most important work in prose (and the superb contextual resources that accompany it) is essential reading for a new generation. We are fortunate to have this new edition of A Youth in Germany as a text for our consideration and meditation.

(This post first appeared on the Stage Write blog on August 5, 2024.)

Comments