A Few Words About Dachau

- Richard Byrne

- Aug 9, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 13, 2025

The announcement that U.S. Vice President JD Vance, and his wife, Usha Vance, would visit the memorial site of the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau in mid-February made me uneasy.

Dachau is the site of a moral abyss. Yet there is an awkward and unavoidable political choreography involved in any such visit – small talk at the gate, a peek at the vast exhibit cataloguing the atrocities committed there, and an inevitable wrestling with an outsized wreath at a memorial wall.

Politics is saying. A saying that is cast not merely in words, but in gestures.

In a place such as Dachau, where words add so little to the ineluctable meaning of the memorial, any and all gestures loom even larger still.

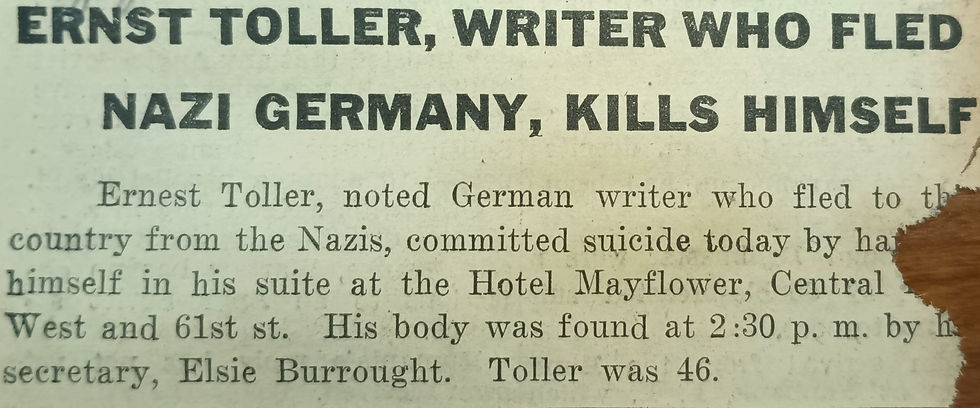

When I was writing my play Hotel Mayflower, which is set in the landscape of ascendant fascism and political exile that gripped the world in 1939, Dachau was a shadow and a stain with which I had to reckon as a dramatist to tell the story.

I discovered that Dachau is a place with a complicated history.

The world knows the town as the site of KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau. Yet it has another history that was forged 14 years before the Nazis created their first concentration camp there. It was a tale of leftist triumph amidst the ebullient fervor and dashed hopes of the Bavarian Soviet Republic (Räterepublik Baiern) of 1919.

In April of that year, a young writer-turned-political leader named Ernst Toller rallied a small force to block the progress of reactionary “Freikorps” forces – many of whom would later become players in the Nazi movement – as they closed in on Munich to crush its revolutionary government.

The opposing sides clashed unexpectedly at Dachau. In the end, munitions workers at the factory in the town – including a number of women – joined Toller’s troops to win the day for the Räterepublik. It was the single military triumph that the revolutionary forces could claim – and it transformed Toller into a figure of global renown as the “victor of Dachau.”

In Hotel Mayflower, Toller tells the story of the Bavarian Soviet Republic as a newspaper would cover a boxing match in response to young (and then-unknown) Beat Generation writer William Burroughs’ challenge that he do so. Ilse Burroughs – the writer’s first wife – tries to explain the battle of Dachau more usefully to her husband.

ILSE: You left out the most important part.

TOLLER: Did I?

ILSE: (Over.) Dachau

BURROUGHS: What’s Dachau?

ILSE: (Over BURROUGHS.) A town north of Munich.

TOLLER: (Over ILSE.) Not the most important …

ILSE: (To BURROUGHS.) Herr Toller defeated the troops who invaded Munich at Dachau.

TOLLER: We stopped them for a few days only.ILSE: Even after the Communists deposed you, you kept faith with the people. (To BURROUGHS.) Herr Toller took soldiers north to meet the invaders. They will never forget how a poet bloodied their nose.

TOLLER: At Dachau, the people won the victory.

ILSE: Dachau is why they want you dead. You fought them and beat them.

In the hours that followed his visit, the Vice President’s brief stop at Dachau took a perverse and strident turn away from the logic that compels leaders to turn up at the memorial.

First, Vance made a rhetorically incendiary speech at the Munich Security Conference. And as a writer attuned to the specific history and context of Dachau, his unabashed assertion that Germans – and other Europeans – must be prevented from erecting bulwarks against the forces that created Dachau and every other Nazi death camp was shocking.

To say that “[t]here’s no room for firewalls” only a day after visiting Dachau is an act of negation. A proclamation that whatever lessons such a place can teach us are irrelevant.

And then to meet later that day with the head of Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) – a party which has officially been classified by that nation’s domestic intelligence service as a “‘suspected’ far-right extremist organization?” We have moved at terrifying speed past negation into something much darker.

Reaction to Vance’s words and gestures was swift, but it was impossible to miss U.S.

Czech writer Milan Kundera once observed that “the struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” And Rubio’s words were a pungent example of how power asserts its perceived right to erase memory.

Face the Nation host Margaret Brennan pointed out both the context of where Vance chose to make his remarks (a country where the Nazis had weaponized “free speech” to conduct a genocide) and the Vice President’s choice to meet with a political party steeped in fascist rhetoric. Rubio replied:

Free speech was not used to conduct a genocide. The genocide was conducted by an authoritarian Nazi regime that happened to also be genocidal because they hated Jews and they hated minorities and they hated those that they ... They had a list of people they hated, but primarily the Jews. There was no free speech in Nazi Germany. There was none. There was also no opposition in Nazi Germany, they were a sole and only party that governed that country. So that's not an accurate reflection of history.

The founding of Dachau in 1933 as the first Nazi concentration camp – and the reasons for its creation – are enough to refute Rubio’s assertions.

There was an opposition to the Nazi regime in 1933. Indeed, Dachau was created as the place to imprison its most prominent members within weeks of the Nazis taking power.

As a leading antifascist playwright, poet and activist, Ernst Toller was one of the names at the top of the list for arrest. The police arrived at his apartment in Berlin on February 27, 1933 – the night of the Reichstag Fire – to seize him.

By sheer luck, Toller was out of the country when Brownshirts came for him. Friends warned him not to return. He never set foot in Germany again.

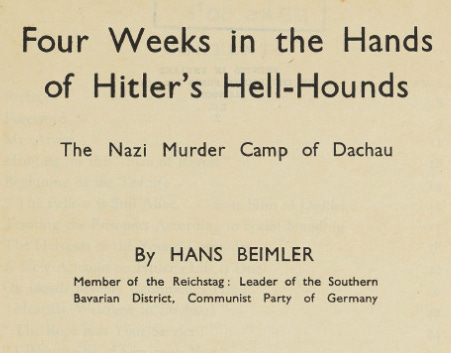

Hans Beimler from Reichstag Directory (1932) / Title Page of Four Weeks in the Hands of Hitlers Hell-Hounds: The Nazi Murder Camp of Dachau (Both Images Public Domain)

As I was writing Hotel Mayflower, I sought to get to the bottom of any tangible connection between the Dachau of 1919 and the Dachau of 1933.

In his essay, “‘We’ll Meet Again in Dachau’: The Early Dachau SS and the Narrative of Civil War,” (Journal of Contemporary History, 2010), Christopher Dillon had some answers. He noted that “[t]here is nothing to suggest that Dachau’s place in Left mythology had any role in the decision to site Munich’s concentration camp there; the decisive factor was the vacant factory premises.” Yet he adds that “its symbolism appealed to the Nazi spirit.”

Dillon’s article also pointed me to an astonishing document: An early insider account of Dachau written by one of its first prisoners: Hans Beimler, a Communist Party member of the Reichstag from Bavaria.

Beimler was arrested in early April 1933 and imprisoned in Dachau. By May 9th, he had managed to escape. His account of what he saw in his few weeks appeared in August 1933. It appeared in English as Four Weeks in the Hands of Hitlers Hell-Hounds: The Nazi Murder Camp of Dachau. (Beimler died in 1936 fighting on the Republican side of Spain’s Civil War.)

Four Weeks is a tale of brutal murder and torture aimed not only at breaking prisoners, but literally driving them to suicide. It is certainly the first detailed account from inside the camp, filling in fuzzier reports appearing in outlets such as the New York Times over the first months of Dachau’s existence.

Indeed, Dillon points to Beimler as perhaps the most prominent connection between the 1919 victory at Dachau and the events of 1933. In a speech at the last Communist Party rally in Munich at the Circus Krone in February 1933, Beimler ended with a promise that his compatriots would happily battle the Nazis – and picked the precise spot: “We’ll meet again in Dachau!”

As soon as March 23, before Beimler even had been arrested, the reactionary Dachauer Zeitung had picked up on his battle cry and turned it inside out:

[Beimler] was right – but in a completely different way …Dachau was once again to become the base for every Red cell bent on transforming our German Fatherland into a communist ‘paradise.’ Now these gentlemen are indeed together again in scenic Dachau – in the concentration camp at the German Works site. But instead of ruling, they are to perform honest work.We’ll meet again in Dachau … proving that world’s history is God’s court!

As I say, a complicated history that we must approach with care. And humility.

"There are no small fascisms, there are no small, benign Nazisms. That is what I try to talk about in my books, the importance of remembering." - Daša Drndić

We find ourselves now in a moment when some of worst actors in American political life openly offer up Nazi salutes in public. Despite a generalized horror this creates in a vast majority of Americans, these gestures also continue to meet with an inexplicable somnolence (or even a pronounced desire to wish them away) from mainstream media outlets. It seems that they cannot simply and clearly name the thing that is happening as the thing that is happening.

Yet as flagrant Nazism slips into becoming a tolerated currency in our discourse, it is important to acknowledge that the mechanisms of totalitarianism in any form vary little in their actual functioning.

One of the most striking formulations of this thought is found in author Victor Serge’s 1945 essay, “The Tragedy of the Soviet Writers.” Serge fastens on a collection of poems by French Resistance writers such as Louis Aragon and Paul Éluard – who fought against Nazism, and yet supported and defended the darkest acts of Stalinist suppression in the years before World War II.

Serge wonders what happens inside the mind of poets who fiercely and bravely battle one sort of totalitarianism, and yet insist upon their duty to “praise the hangman, praise the torturer” working in another repressive regime, and he concludes:

‘What is truth?’ asked Pontius Pilate of the condemned man. Thousands of men formed by the intellectual disciplines of scientific thought – it seems – reply in fact: ‘It is the command of the Leader of my party.’ This is the death of intelligence, the death of ethics.

I have visited Dachau twice now. Not only the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site, but also the Kochwirt restaurant on its town square. It was on this spot, from a patio overlooking that public space, that Ernst Toller addressed the triumphant troops who won the victory of Dachau on April 16, 1919. Gazing down from the restaurant patio onto the empty space below, I could imagine it full of workers flushed with their brief but heady victory as Toller spoke.

The concentration camp memorial site in Dachau is once again a ferocious battleground — a front line in the fight of memory against forgetting and oblivion. It will survive any gestural offenses committed against it, no matter how hollow. The deadly crimes committed here make Dachau hallowed ground. A space in which memory must be defended at all costs.

Yet it is essential to remember that the struggle of humans to remember when power attempts to erase and forget history also must encompass sites of victory and hope. As Toller wrote in his 1933 memoir, A Youth in Germany:

Me, the “victor of Dachau?” No, the workers and soldiers of the Soviet Republic fought victoriously, not their leaders.... They did not wait for a rallying cry.; they actually formed a united front of workers.

This essay relies on material contained in an earlier essay I have written: Dachau 1919 and Dachau 1933.

Read more about Hotel Mayflower — and the bilingual edition of the play from Moloko Print.

(The essay first appeared on the Stage Write Substack on February 25, 2025.)

Comments